3.6 Process address space

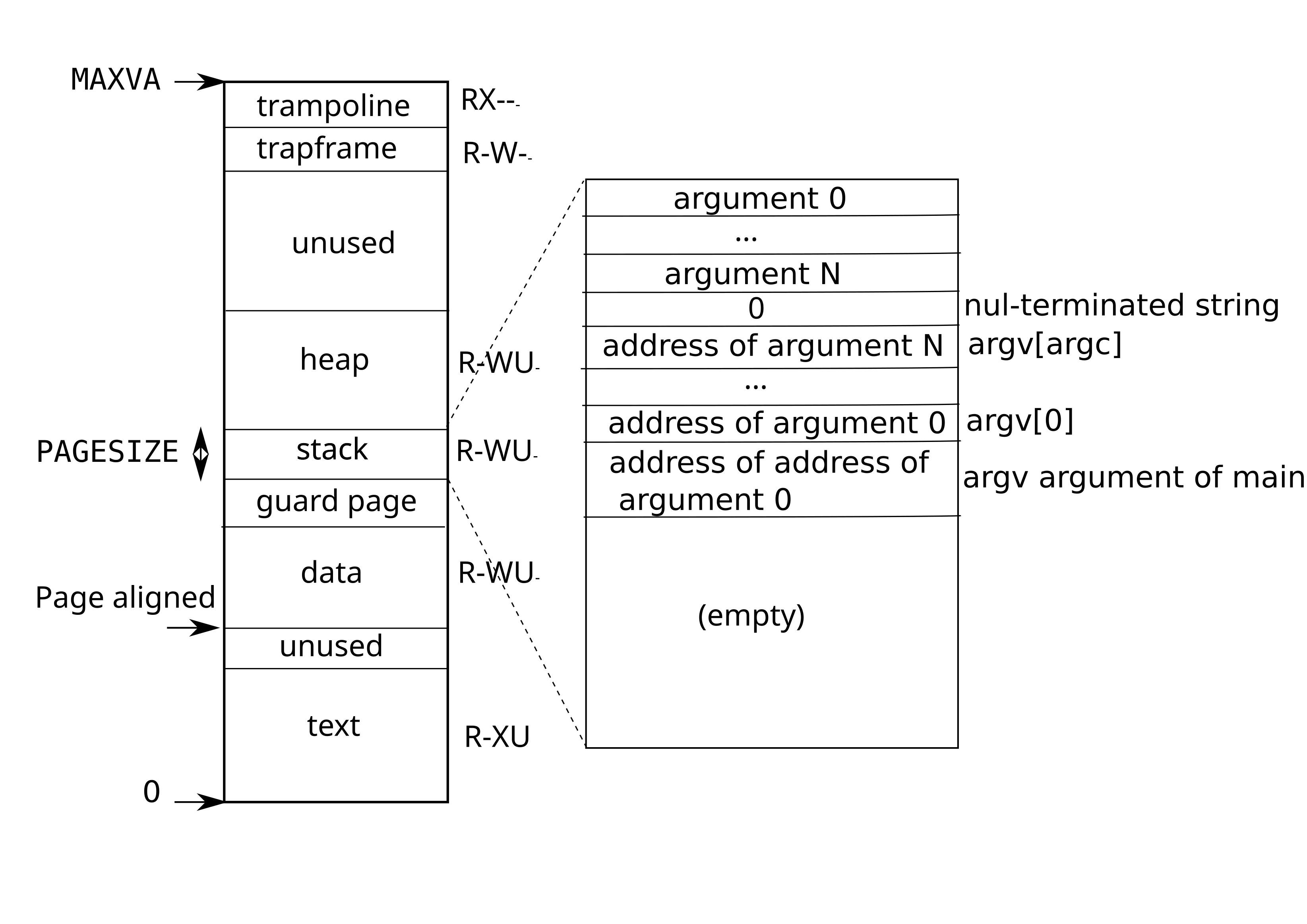

Each process has its own page table, and when xv6 switches between processes, it also changes page tables. Figure 3.4 shows a process’s address space in more detail than Figure 2.3. A process’s user memory starts at virtual address zero and can grow up to MAXVA (kernel/riscv.h:379), allowing a process to address in principle 256 Gigabytes of memory.

A process’s address space consists of pages that contain the text of

the program (which xv6 maps with the permissions PTE_R,

PTE_X, and PTE_U), pages that contain the

pre-initialized data of the program, a page for the stack, and pages

for the heap. Xv6 maps the data, stack, and heap with the permissions

PTE_R, PTE_W, and PTE_U.

Using permissions within a user address space is a common technique to

harden a user process. If the text were mapped with

PTE_W, then a process could accidentally modify its own

program; for example, a programming error may cause the program to

write to a null pointer, modifying instructions at address 0, and then

continue running, perhaps creating more havoc. To detect such errors

immediately, xv6 maps the text without PTE_W; if a program

accidentally attempts to store to address 0, the hardware will refuse

to execute the store and raises a page fault (see

Section 4.6). The kernel then kills the process and

prints out an informative message so that the developer can track down

the problem.

Similarly, by mapping data without PTE_X, a user program

cannot accidentally jump to an address in the program’s data and start

executing at that address.

In the real world, hardening a process by setting permissions carefully also aids in defending against security attacks. An adversary may feed carefully-constructed input to a program (e.g., a Web server) that triggers a bug in the program in the hope of turning that bug into an exploit [12]. Setting permissions carefully and other techniques, such as randomizing of the layout of the user address space, make such attacks harder.

The stack is a single page, and is shown with the initial contents as

created by exec. Strings containing the command-line arguments, as

well as an array of pointers to them, are at the very top of the

stack. Just under that are values that allow a program to start at

main as if the function main(argc,

argv) had just been called.

To detect a user stack overflowing the allocated stack memory, xv6

places an inaccessible guard page right below the stack by clearing

the PTE_U flag. If the user stack overflows and the

process tries to use an address below the stack, the hardware will

generate a page-fault exception because the guard page is inaccessible

to a program running in user mode. A real-world operating system might

instead automatically allocate more memory for the user stack when it

overflows.

When a process asks xv6 for more user memory, xv6 grows the process’s

heap. Xv6 first uses kalloc to allocate physical pages.

It then adds PTEs to the process’s page table that point

to the new physical pages.

Xv6 sets the

PTE_W,

PTE_R,

PTE_U,

and

PTE_V

flags in these PTEs.

Most processes do not use the entire user address space;

xv6 leaves

PTE_V

clear in unused PTEs.

We see here a few nice examples of use of page tables. First,

different processes’ page tables translate user addresses to different

pages of physical memory, so that each process has private user

memory. Second, each process sees its memory as having contiguous

virtual addresses starting at zero, while the process’s physical

memory can be non-contiguous. Third, the kernel maps a page with

trampoline code at the top of the user address space (without

PTE_U), thus a single page of physical memory shows up in

all address spaces, but can be used only by the kernel.